Why Trump’s tariffs have failed

Who is really paying the cost—and why the Greenland tariff threat rings hollow

Over the past few days, Donald Trump has threatened to slap tariffs on countries opposing the annexation of Greenland. On Saturday, that threat became policy: a 10 percent tariff—set to rise to 25 percent—on eight European countries that have deployed troops to the island, to remain in place “until the United States has acquired Greenland.”

Economists have long viewed broad, open-ended tariffs—applied indiscriminately across countries and sectors—as a blunt and largely self-defeating tool. Yet, one year into Trump’s new term, the U.S. economy does not yet display the kind of damage such policies typically inflict over the medium run. Inflation has risen, but not dramatically. Unemployment has remained broadly stable. Customs revenues have surged. And trading partners have, so far, largely refrained from retaliation.

So have the tariffs worked? No.

In what follows, I explain why the most harmful effects of Trump’s tariffs have yet to fully surface, who has actually borne their cost so far, what is likely to come next—and why the latest tariff threat against Europe is, in economic terms, far less powerful than it appears.

Why the U.S. economy has “withstood” the tariffs

The U.S. economy’s apparent resilience is not evidence that the tariff strategy has succeeded. It is the byproduct of a mix of structural conditions and short-term contingencies that have, for now, softened or obscured the costs imposed by trade barriers.

Measurement issues

Any serious evaluation has to start with the data. Over recent months, the reliability of U.S. macroeconomic statistics has been undermined by institutional disruptions. The extended federal government shutdown, which lasted from October 1 to November 12, disrupted routine data collection, with particularly visible effects on inflation statistics. For October, the Bureau of Labor Statistics was unable to gather a substantial share of the price observations normally used to construct the Consumer Price Index.

These technical problems were compounded by overt political interference. After the release of employment figures deemed unfavorable by the administration, the BLS director was removed and replaced by E.J. Antoni, a contributor to Project 2025. Shortly after his appointment, Antoni publicly questioned the credibility of U.S. labor statistics and suggested suspending their publication altogether.

The result is a degraded informational environment in which the economic consequences of policy choices—including tariffs—are more likely to surface in official data only with delays, or in muted and incomplete form.

TACO: the pattern of retreat

A second reason Trump’s tariffs have generated fewer immediate effects than many expected is that the most aggressive measures were never fully carried through. Tariff hikes were repeatedly delayed, softened, or quietly reversed once their domestic costs became harder to ignore. In November, for instance, several duties were rolled back after they began pushing up grocery prices.

At the same time, the administration carved out sweeping exemptions for key countries and industries. Nowhere was this more consequential than in the highly integrated North American auto sector. A uniform 25 percent tariff would have rippled through the entire supply chain, inflicting immediate damage on U.S. manufacturers as well as their Canadian and Mexican counterparts. Within days, imports from Canada and Mexico covered by the USMCA were exempted, effectively defanging one of the administration’s most loudly proclaimed trade measures.

This outcome was always predictable. Fully enforcing the tariffs Trump announced would have imposed immediate and severe costs on U.S. firms, quickly turning the trade war into a political liability. The strategy, instead, has been to announce maximalist positions and retreat once the domestic fallout becomes too visible—often without securing any meaningful concessions in return.

In financial markets, this pattern has become so routine that it now has a name. Investors refer to it as TACO—“Trump Always Chickens Out”—shorthand for the expectation that the most economically damaging versions of his policies will eventually be walked back.

None of this means the tariffs currently in place are benign. They remain elevated and distortionary. But it does mean that their most destructive form has, so far, been avoided.

That should not be mistaken for success. There are strong reasons to think that a large share of the damage has merely been deferred. Higher prices, weaker productivity, and softer employment are not disappearing—they are being pushed into the future, with many of the costs likely to become visible in 2026.

Limited retaliation—for now

So far, the United States’ major trading partners have largely held back from broad retaliatory measures. Part of the reason is straightforward: tariff retaliation is costly for those who impose it. Hitting back means hurting one’s own consumers and firms, not just the adversary - as I explained in a previous post (“Trump didn’t win, Europe didn’t lose”).

But restraint has also been strategic. In the current geopolitical context, Europe has a strong incentive to avoid—or at least postpone—further U.S. disengagement from NATO’s eastern flank, which remains critical for deterrence against Russia.

There is also a structural point that rarely enters public discussion. Even as the world’s largest economy, the United States accounts for only about 13 percent of global goods imports and less than 10 percent of exports. That limits Washington’s leverage. Many countries affected by U.S. tariffs have been able to absorb the shock without fundamentally reshaping their trade strategies.

China is a partial exception. Rather than responding with symmetric tariffs, Beijing has relied on more targeted tools, most notably restrictions on rare earth exports. Beyond that, no major trading partner has chosen to escalate into a full-scale tariff war with the United States.

Front-loaded imports

The lack of retaliation has helped sustain the impression that tariffs were delivering leverage at little cost. In reality, much of that apparent resilience reflects preemptive behavior by U.S. firms—well before many of the tariffs formally took effect.

Following Trump’s re-election in late 2024, American importers began pulling purchases forward, building inventories to get ahead of the announced measures. The pattern was most visible in high-value or hard-to-substitute goods—such as gold imported from Switzerland and weight-loss drugs from Ireland—but it quickly spread across a wide range of products.

Estimates from the Penn Wharton Budget Model suggest that this front-loading allowed U.S. importers to avoid up to $6.5 billion in tariffs between January and May 2025—roughly 13 percent of the new tariff burden. As long as those pre-tariff inventories remain on shelves, retailers face little pressure to raise prices.

That helps explain why inflation in imported goods stayed muted longer than economists expected. But the effect is temporary by construction. Once inventories are drawn down, higher costs begin to move through supply chains and, ultimately, into consumer prices.

Who has been paying the tariffs so far? Americans

Yale’s Budget Lab estimates that between January and August 2025 the U.S. collected $146 billion in net tariff revenue. That’s total customs revenue from all tariffs—not just the ones introduced this year. Before the new round, the effective average tariff rate was 2.4 percent, bringing in about $7 billion a month.

If the 2025 tariffs stay in place, they would raise more than $2.7 trillion over the next decade on a conventional score. But that headline number overstates the fiscal “win”: tariffs also slow output, which means less revenue from other taxes and a smaller net gain for the budget.

So yes, tariff receipts are up. But higher receipts don’t mean foreign producers are paying. Tariffs on Chinese and European goods may be flowing into the U.S. Treasury, yet the burden is not, in any simple sense, being exported to China, Europe, or America’s other trading partners.

In theory, tariffs paid by U.S. importers can show up in the data through three channels. Foreign suppliers can absorb them by cutting prices and squeezing margins. U.S. importing firms can absorb them through lower profits. Or the costs can be passed through to consumers in the form of higher retail prices.

Only the first channel fits the Trump administration’s claim that foreigners are “paying” the tariffs. The evidence points the other way. Import prices have not declined; if anything, they have ticked up.

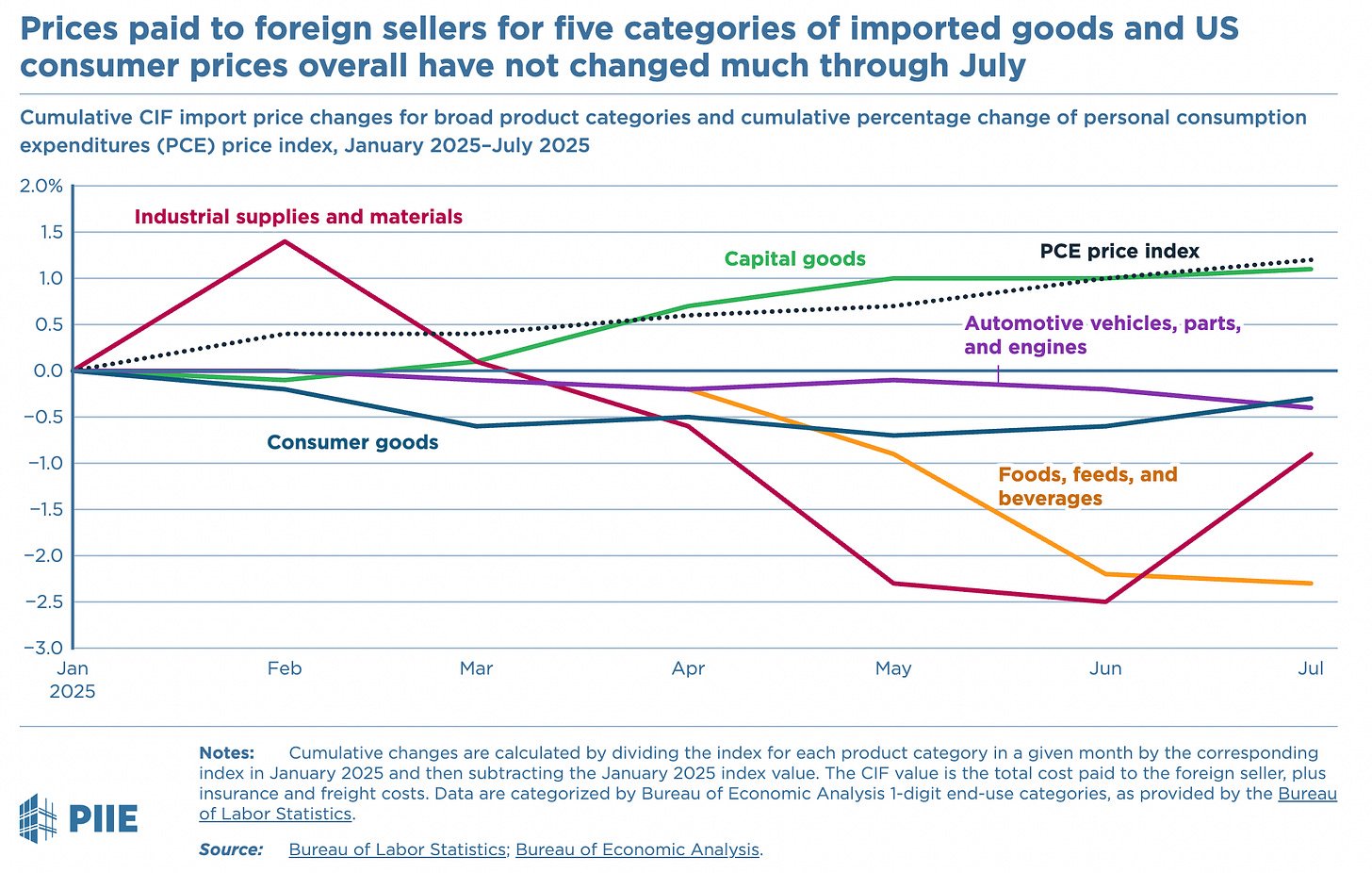

The figure below—produced by the Peterson Institute for International Economics (PIIE) using Bureau of Labor Statistics data—tracks the cumulative evolution of import prices paid to foreign suppliers, including cost, insurance, and freight (CIF), since January 2025 across five major end-use categories. Rising prices make clear that foreign producers are not absorbing the tariffs by cutting margins.

So who is paying the tariffs? As the next sections show, U.S. consumers are already bearing a meaningful share of the burden, as prices have risen across virtually every sector. But higher consumer prices alone are not enough to explain the surge in tariff revenue.

What closes the gap are U.S. importing firms. American importers are absorbing a much larger share of tariff costs than economists initially anticipated. Faced with the extreme policy uncertainty generated by the Trump administration, firms have been slow to pass higher costs through to final prices, choosing instead to compress margins—at least temporarily.

The fact that retail prices have not yet spiked does not mean U.S. consumers are shielded. Inflationary pressures are already evident and are likely to intensify as this absorption phase runs its course.

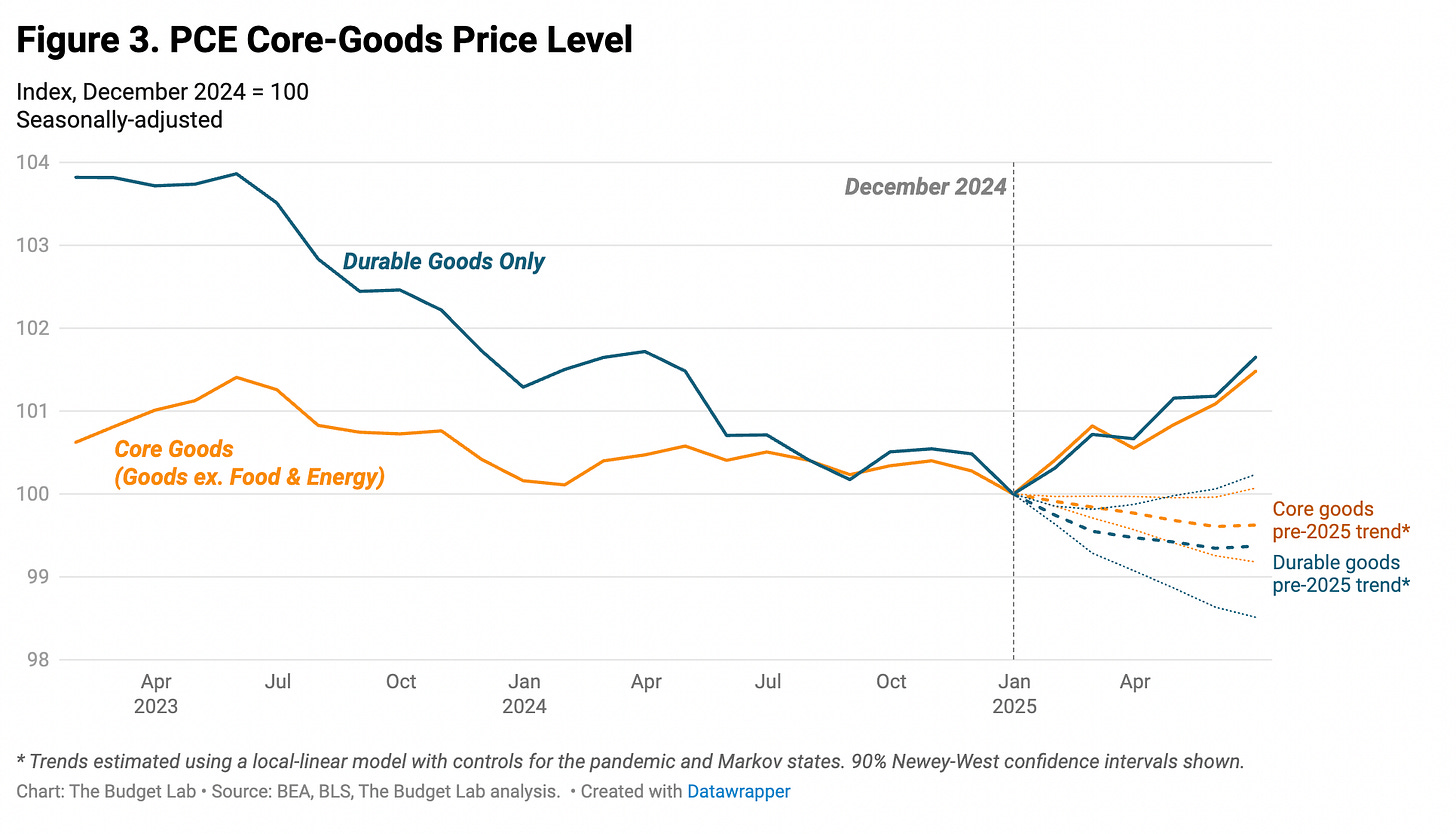

A comparison between observed prices and plausible counterfactuals—constructed by extrapolating pre-2025 trends—helps quantify the damage to consumers. In the first half of 2025, core goods prices in the PCE (excluding food and energy) rose by 1.5 percent, compared with just 0.3 percent over the same period in 2024. The divergence is even more pronounced for durable goods: prices increased by 1.7 percent in the first half of 2025, versus a 0.6 percent decline in 2024. By June, core goods prices were already 1.9 percent above their pre-2025 trend, while durable goods exceeded the counterfactual by roughly 2.3 percent. Both gaps are statistically significant.

The distributional impact is sharply regressive. The average household is estimated to lose around $1,700 per year, while households in the lower part of the income distribution face losses of roughly $900.

The figure below—produced by the Yale Budget Lab using data from the Bureau of Economic Analysis and the Bureau of Labor Statistics—shows the evolution of core goods and durable goods prices relative to their no-tariff counterfactual trends.

Further empirical evidence strengthens this conclusion. For several months, Alberto Cavallo (Harvard University), Paola Llamas (Northwestern University), and Franco Vázquez (Universidad de San Andrés) have been tracking thousands of retail prices in real time. Their estimates indicate that average prices of imported goods have increased by roughly 4 percent since early March, and by about 5 percent relative to a counterfactual constructed from pre-2025 trends.

Crucially, domestically produced goods that compete with imports have followed a nearly identical path, with price increases of similar magnitude. Tariffs, in other words, spill over well beyond the goods they formally target, pushing up prices even where no tax is levied directly.

Estimates from the Yale Budget Lab suggest that tariff pass-through to consumer prices—the share of tariff costs ultimately borne by households—stood at around 70 percent in June and is likely to rise toward 100 percent over time. After an initial phase in which firms absorbed part of the shock, tariff costs are increasingly passed on to consumers. At that point, American households face a simple trade-off: either consume less or pay more—at least until U.S. industry develops the highly unlikely and economically inefficient capacity to fully replace imports at home.

Trump’s latest tariffs also contain a particularly self-defeating element. Roughly three quarters of U.S. insulin imports originate in Denmark, largely via Novo Nordisk. The same holds for a substantial share of GLP-1 drugs used to treat obesity, including Ozempic and Wegovy. Targeting Denmark therefore strikes directly at one of the most sensitive supply chains in a country with exceptionally high rates of obesity and diabetes, raising the cost of essential medications for millions of Americans. Few examples illustrate more clearly how tariff “blackmail” ultimately rebounds against the country that deploys it.

The Labor Market

The labor-market effects of tariffs are neither immediate nor straightforward. One of the Trump administration’s stated objectives is to revive manufacturing employment. In practice, however, higher input costs and the resource misallocation induced by trade barriers tend to work in the opposite direction.

As Robert Lawrence has argued in Time, evidence of stagnation—and outright weakening—in U.S. manufacturing is becoming increasingly difficult to ignore. Firms appear more hesitant to hire and to invest domestically, especially in sectors most exposed to tariffs.

The data are broadly consistent with this assessment. Estimates from the Yale Budget Lab indicate that employment in tariff-exposed sectors did increase in 2025, but by less than would have been expected in the absence of the trade war; the difference is not statistically significant. Within manufacturing, the most tariff-sensitive segments registered a modest decline in employment, largely in line with the sector’s overall trajectory.

If the current tariff regime remains in place, the unemployment rate is projected to rise by roughly 0.3 percentage points by the end of 2025 and by about 0.6 percentage points by the end of 2026—corresponding to approximately 460,000 fewer jobs in 2025 alone. Were the tariffs to be struck down by the courts and the revenues refunded, the projected employment loss in 2026 would be roughly cut in half.

AI investments

So far, however, these pressures have not culminated in an outright recession. Part of the reason is that other forces have continued to support aggregate demand and investment in the short run.

One of the forces cushioning the macroeconomic impact of tariffs has been the surge in investment tied to artificial intelligence.

As Jason Furman has noted, during the first half of 2025 spending on data centers, digital infrastructure, and AI-related computing capacity accounted for a strikingly large share of real GDP growth. While these investments represent only a small fraction of total economic activity, they explain most of the expansion observed over the period; without them, growth would have been close to zero.

Sectoral evidence underscores just how unusual this episode has been. U.S. spending on data-center construction has climbed to record highs, with annualized levels around $40 billion, driven by the rapid diffusion of generative-AI applications and the soaring demand for computing power from large technology platforms. This infrastructure boom has supported private investment, employment in construction, and parts of the advanced-services sector, partially offsetting the contractionary effects of tariffs elsewhere in the economy.

Crucially, this does not invalidate economists’ predictions about tariffs. It helps explain their timing. Investment in AI does not remove the costs created by trade barriers; it postpones their full macroeconomic expression, propping up demand while tariff-induced distortions continue to build beneath the surface.

Conclusion

Trump’s tariffs do not trigger sudden crises or spectacular breakdowns. They work slowly and cumulatively, eroding economic efficiency, distorting investment decisions, and reducing consumer welfare over time. That gradualism makes them politically misleading: the costs are real, but delayed—clearly visible in the data, far less so in the public narrative.

The threat of new tariffs against Europe is credible in a narrow, procedural sense: Trump does tend to translate rhetoric into policy. But as a tool of coercion, tariffs are deeply ineffective. They allow the United States to impose modest costs on trading partners only by imposing larger and more persistent costs on itself, hastening productive, financial, and geopolitical adjustments that ultimately leave the U.S. worse off.

Put differently, tariffs are not the decisive instrument Trump portrays. They are a blunt and highly visible political device—well suited to signaling conflict, poorly suited to economic statecraft. They do not generate prosperity. They generate uncertainty and push America’s trading partners to diversify markets, supply chains, and alliances, gradually reducing Washington’s centrality in the global economy. Their primary function is not to compel compliance, but to sustain a narrative of strength that substitutes for strategy while shifting the economic burden of confrontation onto American households and firms.